FFA2020 returns to Brussels with an open debate on rewarding food system sustainability

Mark Titterington, responsible for FFA strategy and partnerships

Monday, Dec 07, 2020

The Forum for the Future of Agriculture returned to Brussels at the end of October with the second of its Online Live events, hosted by the journalist, Jennifer Baker. Participants from across the global FFA network joined the event which was focused on Rewarding sustainability in the food system. In particular, the meeting explored the premise that the future of the food system is likely to rely on two interdependent drivers: the adaptation and reinvention of food system business models; and the development of practices that can generate agri-solutions to climate change which create value for the providers and society at large.

Urgency for action

In his opening address, FFA Chairman, Janez Potočnik, made clear that “Farmers deserve a decent life where they are rewarded for the food they produce and the public goods that they provide”. But he again reiterated the urgency of planning for a sustainable future, citing the recent WWF report which revealed ice sheets melting to their lowest levels since records began alongside an alarming loss of global species and biodiversity since 1970.

The former EU Environment Commissioner repeated his argument that the current market signals do not reflect the true environmental cost of producing food and that there are simply “hard boundaries” to life on this planet. He argued that it is vital that market signals become more aligned with true costs of producing, particularly accounting for the environmental impact, and that innovative actors in the food system, especially growers, should be rewarded for adapting or reinventing their business models to provide public goods, including agri-solutions to climate change.

Adapting and reinventing food system business models

In the panel session on sustainable agri-food business models, which followed Janez Potočnik’s opening address, Organics Europe Brussels Director, Eduardo Cuoco, built on this theme. He framed the discussion from the organic farming perspective, stating that the industrial agriculture model that is currently in place “is generating a vicious circle.” He went on to say that “we need to look at this transition with a holistic approach. To see how policy can support from one side, the agri-food chain to make transition happen and also support the market of those products in the first place” stressing the importance of creating policy that aids in the development of the market. A second fundamental factor is working on consumer behaviour and consumer education and “why it is important that they choose sustainability instead of cheap prices.” Mr. Cuoco believes that retailers can play an important role in this transition in explaining “how the price of a product is built” emphasising that it is not an easy issue. He stressed that food prices are too cheap and when consumers save money with prices, they pay the price elsewhere, pointing to the environmental impacts that our current food system has inflicted on the world.

In a similar vein, Ben O’Brien, Europe Director of Beef+Lamb New Zealand argued that science and technology, and the pace of its development, will always be the determining factor in the reinvention or adaption of business models. He made clear that “change can only happen as fast as is technically possible” and that even then, “… the rate at which people will change their behaviours is dependent upon their incentive to change”. It is clear from ongoing discussion around this point, that where markets fail to provide the incentive to change, public intervention is needed both from a financial compensation as well as regulatory perspective.

Rabobank’s Global Head of Sustainability, Bas Ruiter, built on this, arguing that it will be a collective challenge, involving a coalition of all actors, to drive the change necessary to produce a more resilient and sustainable food system. He stressed that it cannot be the responsibility of one or even a few actors, and that there is an alignment on the need to reflect ‘true pricing’ (the real cost of the goods and services produced) in the price we pay for food. It was clear, for Mr. Ruiter, that this is not happening and, consequently, consumers make different choices. In this respect, he felt that financial institutions, like Rabobank can play a substantive role, in supporting the adaptation or reinvention of food system business models, by linking the price of finance or credit to the sustainability performance of their clients.

Echoing the comments of Mr. Ruiter, delegates to the conference agreed that it was not one food chain actor more than another that should pay for the achievement of greater sustainability in the food system- 65% believed that it was a shared responsibility between the public and private sector and consumers.

Creating shared value from agri-solutions to climate change

The second panel session took a deeper dive into the extent to which agri-solutions to climate change could emerge and how they could create and share additional value, particularly with growers. These solutions range from so-called carbon farming to regenerative and precision agriculture whilst further down the food chain concern improvements in processing, transportation, storage and shelf life.

Responding to the question of how to achieve this, Ulrike Sapiro, Senior Director for Water, Sustainability and Stewardship at The Coca-Cola Company, said, “There isn’t a silver bullet, there will be a number of policy, financial and risk management instruments that will have to play a role and for a very solid policy you need to really assess what are the problems you want to solve and what are the options available”. Nevertheless, she made clear that she believes private sector actors, like The Coca-Cola Company, can and are playing a leading role in embedding sustainability into their supply chains and climate policy. She did say, however, that it will be important to align on and be clear with farmers and policy-makers what sustainability and climate change solutions look like, and – importantly – how they are rewarded.

Echoing the theme of rewarding growers properly for what they do, Marjon Krol, Market and Food Chain Manager at ZLTO, said that whilst, “… many farmers are aware of the needs from society, as long as they are paid only to produce affordable food they [will] lack the resources to invest in the transition”. She provided two examples where a coalition of actors are trying to address this at a local level in the Netherlands.

The first concerns the Biodiversity Monitor, which requires dairy farmers to take action and quantify their contribution to biodiversity enhancements. Supported by local water companies, financial institutions, like Rabobank, NGOs, like WWF, and the regional government, these farmers are rewarded in the form of a price premium on the milk price, reduced land rent, and lower interest rates on credit. The second example concerns carbon farming where an initiative has started with a small number growers who adopt practices designed to sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. They are rewarded with €100 for each tonne of carbon sequestered which is paid for my companies and organisations who want to offset their own unavoidable carbon emissions. Although these examples provide a good indication of what is possible, Ms. Krol was clear that ultimately farmers, “… will not find it easy to transform their business models, if they cannot pay for it”.

And in this respect, Tassos Haniotis, Director of Strategy and Policy Analysis at the European Commission’s Directorate General for Agriculture, argued that the reform of the Common Agriculture Policy will have to play a role in supporting growers in adopting practical measures that really can drive sustainability. For Mr. Haniotis, this involves a particular focus on soil health, where improvements in this area can unlock adjacent benefits in terms of water and biodiversity, as well as the productive capacity of the farm. Although Mr. Haniotis agreed with the urgency of the climate crisis, he also argued that we need to recognise the economic situation we are in, with respect to COVID-19. With the focus on food affordability likely to increase, adjustments to these price signals need to be handled carefully. In this respect, he suggested a two-step approach working to help consumers to understand how their food is produced, and at what cost, to influence purchasing decisions, alongside technology adoption and practice changes that can improve the cost and sustainability of production.

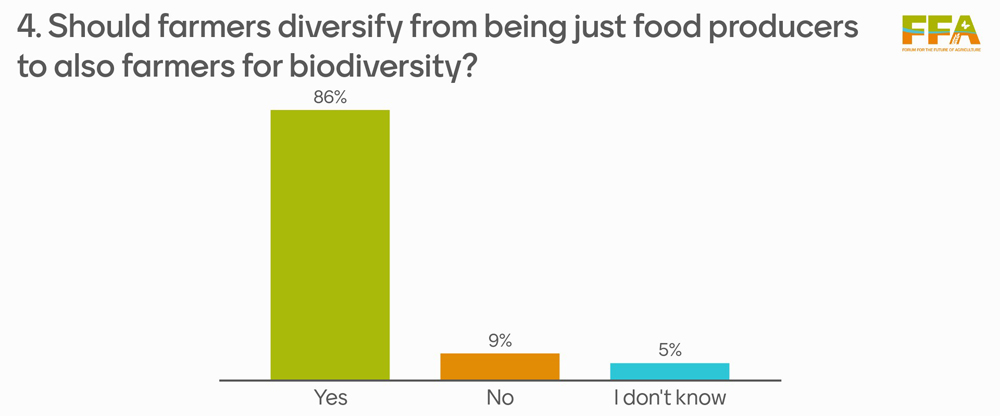

John Gilliland, OBE, Director of Agriculture and Sustainability at Devenish Nutrition, built on this and argued that, in his view the combination of technology and robust monitoring and measurement, was key to understanding and demonstrating how value can be created by taking action to improve farm resilience and sustainability and contributing solutions to climate change. He stressed the importance of striking a balance when running a farm. Economics cannot be prioritised over sustainability and health in the long run as it will impact the quality of the nutrients in the soil and the nutrients of the product. He emphasised the importance of healthy soil for farms trying to reach their own net zero targets and stressed the importance of harmonising the relationship between livestock and the land. One of the most effective practices that he mentioned was introducing Silvopasture, putting trees and animals together in the same area. While seeing no reduction in livestock performance, this allowed the soil trafficability window to increase by seventeen weeks allowing for a significant boost in productivity. Mr. Gilliland dispelled the notion that ruminant agriculture is harmful stating “It is a myth that if you get rid of ruminant agriculture you sort out all the problems, you don’t.” He noted that ruminants play a key role in the inoculation of soil. It is evident from Mr. Gilliland’s success that the relationship between livestock and soil is paramount to the overall quality and output of a farm. The benefit of this alignment between food and environmental sustainability, which Mr. Gilliland alluded to, was borne out by the participants, with nearly 90% of them agreeing that growers should farm for biodiversity as well as food.

Surfacing the challenges but also some solutions

It was clear from this latest FFA2020 Online Live! event that there is an ever-increasing consensus that the price signals in the agri-food system must reflect the true cost to the environment and that growers must be rewarded for the sustainability services they provide. Quite simply, nobody will find the incentive to adapt and reinvent business models, at scale, unless the value is rewarded. As usual in these discussions, there is a lot of alignment on the challenge, and even at a high level on how all actors can work together to solve them. But the discussion at this event also focused on many practical steps that are beginning to be taken. These may still be ‘green shoots’ or ‘lighthouse’ examples but they provide some confidence that different stakeholders may be coming together to reward greater resilience and sustainability in the food system. The remaining question, as always, is the extent of the scale and pace that can be achieved in implementation.

Mark Titterington,

responsible for FFA strategy and partnerships